Association Analysis (2)

Handout 08

Date: 2022-11-20

Topic: Association Analysis

Literature

Handout

Ismay & Kim (2022) Chapter 5 and 6

Association analysis

In many case data analysis is about analyzing association between

variables: measuring the strength of a relationship, testing if the

relationship is significant (or can be attributed to chance because the

relationship is measured using a random sample), describing the

relationship with a mathematical equation.

The objective of this kind of analysis can be predicting or estimating

an output based on one or more inputs or just to examine the

relationships between different variables and the structure of the data.

In this lesson, the emphasis is on the former.

When it is about predicting and estimating there are one response (dependent) variable (the Y-variable) and one or more explanatory (independent) variables (X variables). Problems with a categorical response variable are referred to as classification problems, while those involving a numeric response as regression problems.

Relationships between two categorical variables

Common ways to examine relationships between two categorical variables:

- Graphical: clustered bar chart; stacked bar chart

- Descriptive statistics: cross tables

- Metric to measure the strength of the relation:

- phi coefficent, in case of two binary variables

- Cramer’s V

see: http://groups.chass.utoronto.ca/pol242/Labs/LM-3A/LM-3A_content.htm and use

- Hypotheses testing:

- tests on difference between proportions

- chi-square tests a test to test if two categorical variables are independent

- tests on difference between proportions

Example: PPD LONDON, association between OLD/NEW and

LEASEHOLD/FREEHOLD

Research sub question: is there a dependency between the variables

OLD/NEW and LEASEHOLD/FREEHOLD for properties in London?

The question is answered based on the properties sold in January

2019.

Table 1

Houses sold in London in January 2019,

divided by TYPE and FREEHOLD/LEASHOLD

library(openxlsx)

library(tidyverse)

library(flextable)

library(sjstats)

ppd <- read.xlsx("datafiles/HP_LONDON_JAN19.xlsx")

tab01 <- xtabs(~ TYPE + DURATION, data = ppd)

tab01.01 <- ppd %>%

group_by(TYPE, DURATION) %>%

summarize(COUNT= n()) %>%

spread(DURATION, COUNT) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(TYPE = factor(TYPE))

levels(tab01.01$TYPE) <- list(TERRACED = "T", FLAT = "F",

DETACHED = "D", `SEMI-DETACHED` = "S")

ft <- flextable(tab01.01) %>%

autofit()

ftTYPE | F | L |

|---|---|---|

DETACHED | 35 | 2 |

FLAT | 7 | 775 |

SEMI-DETACHED | 121 | 4 |

TERRACED | 420 | 22 |

#phi(tab01)

#cramer(tab01)

#chisq.test(tab01)Note. As can be seen in this table the distribution over the

Freehold and Leashold categories differ for the different types. The

question is, if the association between the two variables is

significant.

The strength of the relationship can be measured by Cramer’s V, this

metric has a value of 0.949 in this case. This means there is a very

strong relationship between TYPE and FREEHOLD/LEASHOLD; if the type is

known good predictions can be made for the FREEHOLD/LEASEHOLD

category.

Example: crime incidents in 2017 in Washington,

D.C.

The file Crime_Incidents_in_2017.csv (source: http://us-city.census.okfn.org/) contains information

about crimes in Washington D.C. in 2017.

To analyse if there is a relationship between the variables METHOD, a

categorical variable with free unique values (GUN, KNIFE and OTHERS),

and SHIFT a categorical variable with three unique values (DAY, EVENING,

MIDNIGHT) a contingency table has been created.

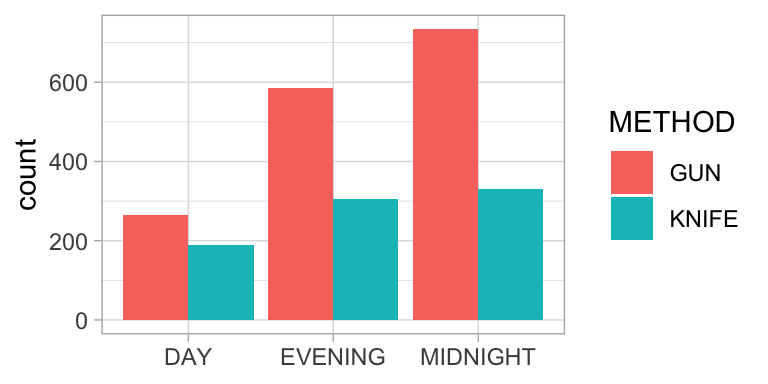

Figure 1

Crimes in Washington D.C. in 2017

crimes <- readr::read_csv("datafiles/Crime_incidents_In_2017.csv") %>%

filter(METHOD != "OTHERS")

tab02 <- xtabs(~ METHOD+SHIFT, data = crimes)

crimes01 <- crimes %>%

filter(METHOD != "OTHERS") %>%

group_by(METHOD, SHIFT) %>%

summarize(COUNT = n()) %>%

spread(SHIFT, COUNT)

ft <- flextable(crimes01) %>% autofit()

#ft <- set_caption(ft, x)

ggplot(crimes, aes(x=SHIFT, group = METHOD, fill = METHOD)) +

geom_bar(position = "dodge") +

xlab(NULL) +

theme_light()

cram02 <- sjstats::cramer(tab02)

chisq02 <- chisq.test(crimes01[,2:4])

chi02 <- scales::comma(chisq02$statistic, accuracy = .01)

p02 <- ifelse(chisq02$p.value<.001, "< .001", paste("=", comma(chisq02$p.value, accuracy=.001)))Table 2

Crimes in Washington D.C. in 2017

ftMETHOD | DAY | EVENING | MIDNIGHT |

|---|---|---|---|

GUN | 266 | 585 | 734 |

KNIFE | 188 | 306 | 330 |

In this example Cramer’s V equals 0.08. The relationship between the two variables is very weak, although it is significant, chisquare(2) = 15.29, p < .001.

Relationship between categorical and numeric variable

Common ways to examine relationships between two categorical variables:

- Graphical: side-by-side boxplots, side-by-side histograms, multiple

density curves

- Tabulation: five number summary/ descriptive statistis per category

in one table

- Hypotheses testing:

- t test on difference between means

- Wilcoxon ranksumtest (also called Mann Whitney U-test) (also applicable in the case of small samples)

- t test on difference between means

Example: comparison airpollution between Amsterdam and

Rotterdam

A comparison of the difference between airpollution caused by PM10 in

Amsterdam, location Einsteinweg and Rotterdam, location Statenweg. The

comparison is based on the figures from 2018 as reported on the RIVM website.

library(scales)

airq <-

read_csv("/Users/R/10Rprojects/AirQuality/Output/oaq2018_nl_majorcities.csv") %>%

mutate(DATE = lubridate::date(lubridate::ymd_hms(tijdstip))) %>%

filter(component == "PM10", locatie %in% c("Amsterdam-Einsteinweg", "Rotterdam-Statenweg"),

waarde >= 0,

DATE >= "2018-01-01", DATE <= "2018-12-31") %>%

select(DATE, TIME = tijdstip, CITY = city, LOCATION = locatie, COMPONENT = component, VALUE = waarde, AQI = LKI)

airq_daily <- airq %>%

group_by(DATE, CITY, LOCATION) %>%

summarize(AVG_VALUE = mean(VALUE, na.rm = TRUE))

airq_table <- airq_daily %>%

group_by(CITY, LOCATION) %>%

summarize(COUNT = n(),

MINIMUM = min(AVG_VALUE),

Q1 = quantile(AVG_VALUE, .25),

MEDIAN = median(AVG_VALUE),

Q3 = quantile(AVG_VALUE, .75),

MAXIMUM = max(AVG_VALUE),

AVERAGE = round(mean(AVG_VALUE), 2),

SD = round(sd(AVG_VALUE), 2))

M_ams <- comma(mean(airq_daily$AVG_VALUE[airq_daily$CITY == "Amsterdam"]), accuracy = .1)

M_rot <- comma(mean(airq_daily$AVG_VALUE[airq_daily$CITY == "Rotterdam"]), accuracy = .1)

SD_ams <- comma(sd(airq_daily$AVG_VALUE[airq_daily$CITY == "Amsterdam"]), accuracy = .1)

SD_rot <- comma(sd(airq_daily$AVG_VALUE[airq_daily$CITY == "Rotterdam"]), accuracy = .1)

airq_daily_wide <- airq_daily %>%

select(DATE, CITY, AVG_VALUE) %>%

spread(CITY, AVG_VALUE) %>%

na.omit()

ttest <- t.test(airq_daily_wide$Amsterdam,

airq_daily_wide$Rotterdam,

paired = TRUE)

tvalue <- comma(ttest$statistic, accuracy=.001)

pvalue <- ifelse(ttest$p.value < .001, "< .001",

paste("=", comma(ttest$p.value, accuracy=.001)))

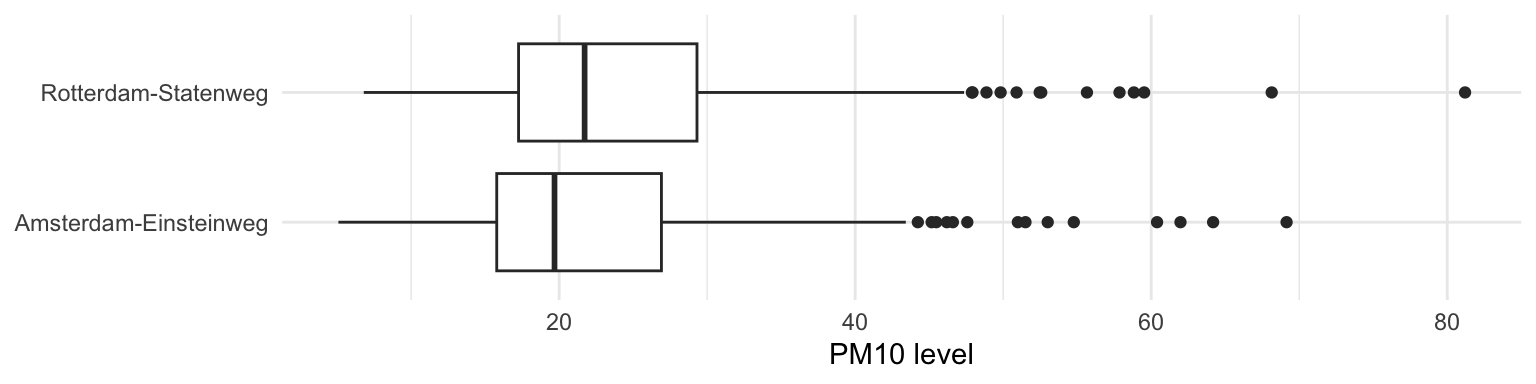

dfvalue <- round(ttest$parameter)Figure 2

Daily average PM10 levels in 2018 on a location in Amsterdam and a

location in Rotterdam

ggplot(airq_daily, aes(x=LOCATION, y = AVG_VALUE)) +

geom_boxplot() +

coord_flip() +

xlab(NULL) +

ylab("PM10 level") +

theme_minimal() Note. Overall air quality in Rotterdam is worse than in

Amsterdam.

Note. Overall air quality in Rotterdam is worse than in

Amsterdam.

Table 3

Summary statistics daily PM10 levels

flextable(airq_table) %>% autofit()CITY | LOCATION | COUNT | MINIMUM | Q1 | MEDIAN | Q3 | MAXIMUM | AVERAGE | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Amsterdam | Amsterdam-Einsteinweg | 363 | 5.086957 | 15.78333 | 19.68750 | 26.91042 | 69.14583 | 22.45 | 10.05 |

Rotterdam | Rotterdam-Statenweg | 365 | 6.800000 | 17.25833 | 21.72083 | 29.31250 | 81.20417 | 24.32 | 10.55 |

A paired t-test is used to investigate whether the daily average values in Amsterdam-Einsteinweg differ from these in Rotteram-Statenweg. Based on this test it can be concluded that the difference between the daily values in Amsterdam (M = 22.5, SD = 10.0) and Rotterdam (M = 24.3, SD = 10.5) is significant, t(362) = -8.847, p < .001.

Relationship between two numerical variables

Common ways to examine relationships between two numerical variables:

- Graphs per variable in order to verify if there are any outliers

(boxplots / histograms).

- Table: summary statistics per variable; verify if there are missing

data.

- Graphical: Scatterplot to graph the relationship between the two

variables. Verify if the graph supports that there exists a linear

relationship and examine if there are outliers.

- Measure of linear association: correlation coefficient.

Notice: statistical association is not the same as a causal relation!!

- Describing the relationship using a mathematical model: linear regression analysis.

Example: Dutch cars

The RDWregr.xlsx file contains data of a number of vehicles including the mass and the selling price.1 It may be assumed that there is a relationship between mass and selling price.

1. Generate a table with the most important statistics concerning the two variables.

2. Create boxplots.

3. Create a scatterplot; examine the outliers; does the graph support the assumption about a relationship between mass and selling price.

4. The strength of the relationship can be measured with the correlation coefficient r (see below); what’s the value of r (use Excel function correl() )?

5. The relationship can be described by a mathematical equation; right click on the dots in the graph and choose the option to plot the best fitting line and display the equation on chart.

Correlation coefficient

The correlation coefficient r is a measure for the strength of a linear relationship between two variables. More about how to interpret a correlation coefficient can be found on this website .

Significant correlation

Even when there is no correlation between two variables the correlation coefficient calculated based on a sample will not be 0. That’s why it is quite common to use a significance test to test whether the r value differs significantly from 0. More about this test can be found here.

Least square regression

Video.

In Excel, the equation of the OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) regression

line can be found in different ways:

- Plotting the regression line and its equation in the

scatterplot.

- Using menu choice: data/data analysis/regression.

- Using formulas to calculate the intercept (formula: intercept) and the

slope (formula: slope) of the regression line.

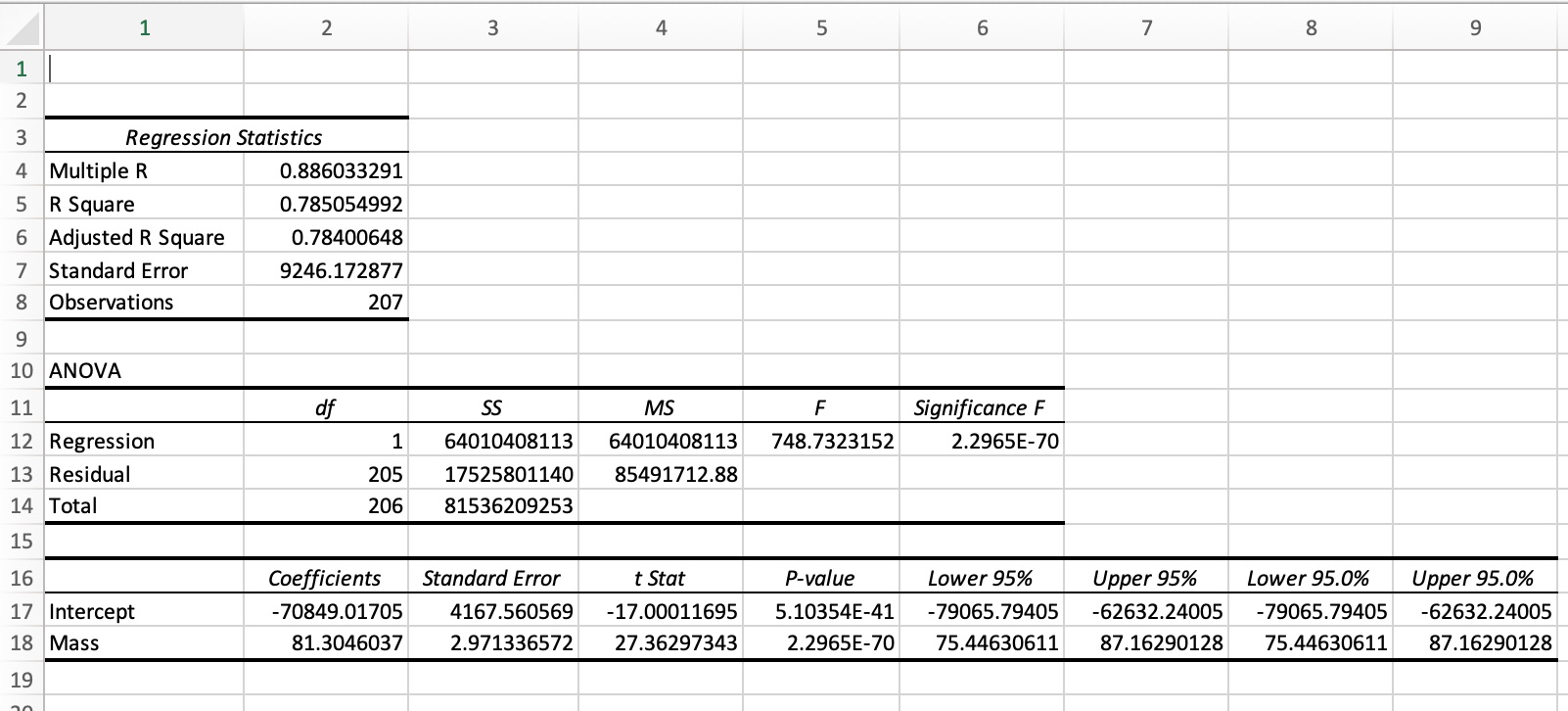

MS Excel regression output

Figure 3 shows the MS Excel regression output for the Dutch car examples (see abve).

Figure 3

Regression output created with MS Excel  Note. Menu choice in Excel: data/Data

Analysis/Regression. To use this option, first activate the Data

Analysis Toolpack in MS Excel.

Note. Menu choice in Excel: data/Data

Analysis/Regression. To use this option, first activate the Data

Analysis Toolpack in MS Excel.

The regression model in the example output in figure 4 can be

described by the equation:

CATALOG PRICE = -70,849 + 81.30 x MASS, where

MASS is the mass of the car in kg, and

CATALOG PRICE is the catalog price in euro.

Figure 4

Regression output RDW example

rdw <- openxlsx::read.xlsx("datafiles/RDWregr.xlsx")

rdw_linmod <- lm(Catalog_price ~ Mass, data = rdw)

summary(rdw_linmod)

Call:

lm(formula = Catalog_price ~ Mass, data = rdw)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-47701 -4551 -765 4342 50948

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -70849.017 4167.561 -17.00 <2e-16 ***

Mass 81.305 2.971 27.36 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 9246 on 205 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7851, Adjusted R-squared: 0.784

F-statistic: 748.7 on 1 and 205 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16It’s also possible to use functions from other packages. The ‘moderndive package’ comes, among others, with some functions to create output for a regression analysis.

Figure 5

Regression output RDW example using moderndive::

rdw <- openxlsx::read.xlsx("datafiles/RDWregr.xlsx")

rdw_linmod <- lm(Catalog_price ~ Mass, data = rdw)

moderndive::get_regression_table(rdw_linmod)Assessing the regression model

After generating a regression model it is important to assess the model. This is done to judge whether the model fits the data and, in case of comparing models, which model fits the data best.

Coefficient of determination R2

In case of simple linear regression, i.e. with just one X-variable, the

R2 value is the correlation coefficient squared. In a multiple

regression setting it’s more complicated.

In general, the following equation holds: R2 = \(\frac{variation\ of\ the\ model\ Yvalues\ around\ the\ mean\ Yvalue}{variation\ of\ the\ Yvalues\ around\ the\ mean\ Yvalue}\) = \(\frac{\Sigma(\widehat{Y} - \bar{Y})^{2}} {\Sigma(Y - \bar{Y})^{2}}\)

The denominator of this expression, \(\Sigma(Y - \bar{Y})^{2}\), measures the

total variation in the Y-values around the mean Y-value, while the

numerator, \(\Sigma(\widehat{Y} -

\bar{Y})^{2}\), measures the variation of the

model Y-values (the \(\widehat{Y}\)-values) around the mean

Y-value. The latter is the variation in the Y-values that is explained

by the regression model.

So R2 measures the proportion of the variation in the

Y-values that is explained by the regression model. In all cases: 0

<= R2 <= 1.

The standard error of the estimate

se

The standard error of the estimate is a metric for the spread around the

regression line.

The value can be used to estimate the so-called margin of error if the

model is used to predict a Y-value given the X-value(s). As a rule of

thumb, the margin of error that should be taken in account when

predicting a Y-value is 2xse.

So the smaller the se value the better the model can predict

a Y-value.

To evaluate the value of se, it is compared with \(\bar{Y}\), commonly by dividing

se by \(\bar{Y}\).

P-values of the coefficient(s)

The P-values of the model coefficients are used to determine whether the

different X-variables are significant in the model. Most common

interpretation: a P-value less than .05 indicates that the X-variable is

significant. The test for which this P-value is calculated is:

H0: \(\beta\) = 0

HA: \(\beta\) <> 0,

where \(\beta\) is the coefficient of

the X-variable in question.

Not rejecting H0 means the coefficient of the X-variable

doesn’t differ significantly from 0, in other words Y doesn’t depend

significantly on X.

Assessing the model in the RDW example

R2 = .785, which means that 78.5% of the variation in

catalog prices is explained by the variation in masses.

se = 9246; if the model is used to estimate the catalog

price, based on the mass of a car, a margin of error of 18,492 (2 x

se) should be taken in account. In other words, this model is

not a very good model to predict catalog prices.

The regression coeeficient of the MASS variable (81.3) differs

significantly from 0, p < .001. MASS is a significant

variable.

Multiple linear regression, an example

The buyer of a new car has to pay a special tax. The heigth of this special tax depends on different factors. Aim of this example is to find a model with which the heigth of the special tax for a Toyota can be estimated, based on different characteristics of this car. For this reason a random sample from in the Netherlands registered Toyota’s has been drawn, reference date 2019-06-12; see file toyota_sample.csv.

Table 4

Toyota Sample, first 10 observations

library(tidyverse)

toyota <- read_csv("Datafiles/toyota_sample.csv")

graph01 <- ggplot(toyota, aes(x = SPECIAL_TAX)) +

geom_histogram(fill = "royalblue")

graph02 <- ggplot(toyota, aes(x=CATALOG_PRICE, y =SPECIAL_TAX)) +

geom_point(col = 'royalblue') +

theme_minimal()

linmod00 <- lm(SPECIAL_TAX ~ CATALOG_PRICE, data = toyota)

linmod01 <- lm(SPECIAL_TAX ~ MASS, data = toyota)

linmod02 <- lm(SPECIAL_TAX ~ MASS+CATALOG_PRICE, data = toyota)

flextable::flextable(head(toyota, n=10)) %>%

fontsize(size=9, part="all") %>% autofit()LICENSE_PLATE | BRAND | ECONOMY_LABEL | FUEL_DESCRIPTION | CILINDER_CONTENT | MASS | CATALOG_PRICE | SPECIAL_TAX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

25ZGBP | TOYOTA | D | PETROL | 1,598 | 1,320 | 24,800 | 5,808 |

SB674R | TOYOTA | A | ELECTRICITY | 1,497 | 1,065 | 20,420 | 628 |

KV635K | TOYOTA | A | ELECTRICITY | 1,497 | 1,060 | 20,222 | 519 |

1TPH61 | TOYOTA | A | PETROL | 998 | 945 | 16,063 | 629 |

31TNKR | TOYOTA | B | PETROL | 1,298 | 1,000 | 16,941 | 3,185 |

89TBVX | TOYOTA | C | PETROL | 1,298 | 995 | 17,430 | 3,682 |

36ZNZX | TOYOTA | A | PETROL | 998 | 805 | 10,580 | 678 |

KJ092K | TOYOTA | A | ELECTRICITY | 1,497 | 1,070 | 22,335 | 856 |

HH024S | TOYOTA | A | ELECTRICITY | 1,798 | 1,310 | 31,445 | 667 |

JX218K | TOYOTA | B | PETROL | 998 | 830 | 13,685 | 1,270 |

Data description

The sample contains almost 400 observations.

As a first analysis the correlation coefficients between some of the numeric variables has been calculated.

Table 5 Correlation matrix

cor(toyota[,c("CILINDER_CONTENT", "MASS", "CATALOG_PRICE", "SPECIAL_TAX")],

use="complete.obs") %>% round(3) CILINDER_CONTENT MASS CATALOG_PRICE SPECIAL_TAX

CILINDER_CONTENT 1.000 0.937 0.847 0.531

MASS 0.937 1.000 0.920 0.556

CATALOG_PRICE 0.847 0.920 1.000 0.644

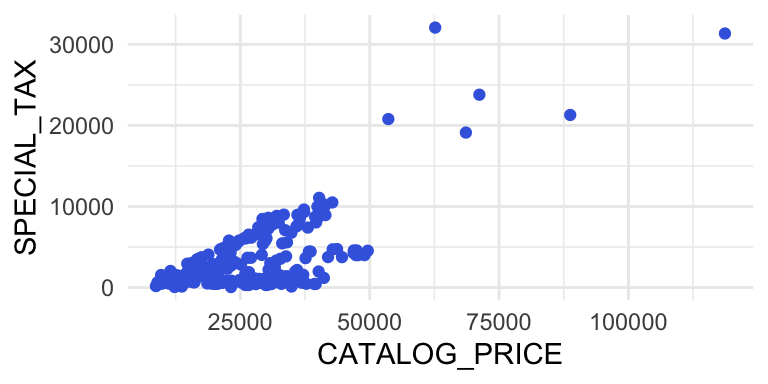

SPECIAL_TAX 0.531 0.556 0.644 1.000As can be seen in Table 6 the variable SPECIAL_TAX has the highest correlation with CATALOG_PRICE. That’s why the first regression model is a simple linear regression model with CATALOG_PRICE as explanatory variable.

Figure 5

Scatterplot, SPECIAL_TAX in euro against CATALOG_PRICE in

euro

graph02

Simple linear models

A first model uses CATALOG_PRICE as explanatory variable.

Figure 6

Simple linear regression model with SPECIAL_TAX ~

CATALOG_PRICE

summary(linmod00)

Call:

lm(formula = SPECIAL_TAX ~ CATALOG_PRICE, data = toyota)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-5202.1 -2457.3 -48.4 1552.8 21545.2

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -2.721e+03 3.548e+02 -7.669 1.36e-13 ***

CATALOG_PRICE 2.114e-01 1.263e-02 16.734 < 2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 2839 on 395 degrees of freedom

(3 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.4148, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4134

F-statistic: 280 on 1 and 395 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16A second model uses MASS as explanatory variable.

Figure 7

Simple linear regression model with SPECIAL_TAX ~ MASS

summary(linmod01)

Call:

lm(formula = SPECIAL_TAX ~ MASS, data = toyota)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-5453.7 -2541.8 -234.7 1467.7 26311.6

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -6396.8549 702.5876 -9.105 <2e-16 ***

MASS 7.6394 0.5753 13.279 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 3080 on 398 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.307, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3053

F-statistic: 176.3 on 1 and 398 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Multiple linear model: SPECIAL_TAX ~ MASS + CATALOG_PRICE

In the next model two explanatory variables ares used: MASS and CATALOG_PRICE.

Figure 8

Multiple Linear Regression Model SPECIAL_TAX ~ CATALOG_PRICE +

MASS

summary(linmod02)

Call:

lm(formula = SPECIAL_TAX ~ MASS + CATALOG_PRICE, data = toyota)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-5166 -2266 -373 1370 20180

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -628.91679 915.16671 -0.687 0.4924

MASS -3.33629 1.34651 -2.478 0.0136 *

CATALOG_PRICE 0.28453 0.03207 8.873 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 2821 on 394 degrees of freedom

(3 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.4238, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4209

F-statistic: 144.9 on 2 and 394 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Although this model uses two explanatory variables which are both moderately correlated with the response variable SPECIAL_TAX, the model is not much better than the simple linear models. The reason for this is that the two explanatory variables are highly correlated with each other. In general it is preferable to use explanatory variables which are not correlated to each other.

Multiple linear model: SPECIAL_TAX ~ CATALOG_PRICE + FUEL_DESCRIPTION

The next model makes use of a dummy variable ELECTRIC (1 = FUEL_DESCRPTION=“ELECTRICITY”, 0 = FUEL_DESCRPTION<>“ELECTRICITY”).

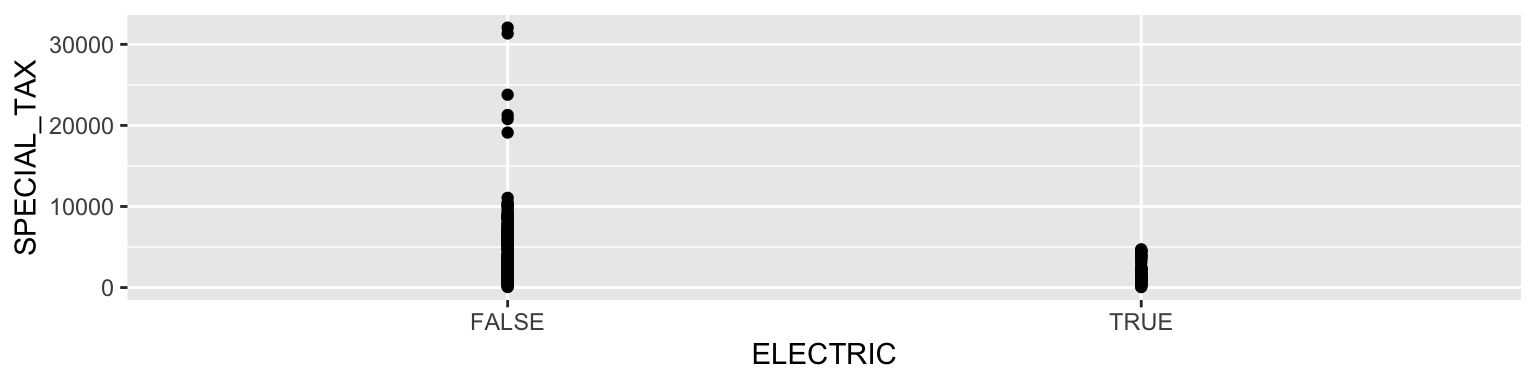

Figure 9

Scatterplot SPECIAL_TAX ~ ELECTRIC

toyota %>% ggplot(aes(x=ELECTRIC, y=SPECIAL_TAX)) +

geom_point()

Figure 10

Multiple Regression Model with a Dummy Variable SPECIAL_TAX ~

CATALOG_PRICE + ELECTRIC

library(dplyr)

toyota<- toyota |>

mutate(ELECTRIC = ifelse(FUEL_DESCRIPTION == "ELECTRICITY", 1, 0))

linmod03 <- lm(SPECIAL_TAX ~ CATALOG_PRICE+ELECTRIC, data = toyota)

summary(linmod03)

Call:

lm(formula = SPECIAL_TAX ~ CATALOG_PRICE + ELECTRIC, data = toyota)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-5431.3 -892.2 -217.6 801.3 16619.8

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -1.965e+03 1.959e+02 -10.03 <2e-16 ***

CATALOG_PRICE 2.779e-01 7.255e-03 38.31 <2e-16 ***

ELECTRIC -4.974e+03 1.637e+02 -30.39 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 1555 on 394 degrees of freedom

(3 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.825, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8241

F-statistic: 928.9 on 2 and 394 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16Note. This model is really an improvement of the simple regression model with CATALOG_PRICE as the only explanatory variable.

In R it is possible to use a catagorical variable as explanatory

variable in a regression analysis. In such a case, R transforms the

catagorical variable in a number of dummies.

For instance, in the Toyota example the categorical variable

FUEL_DESCRIPTION can be added as explanatory variable.

This variable has four unique values: PETROL, ELECTRICITY, DIESEL,

LPG.

R creates three dummy variables, not four. After all, if the value of

three of the four possible dummy variables is known, the fourth is known

as well.

Figure 11

Multiple Regression Model with a Dummy Variable SPECIAL_TAX ~

CATALOG_PRICE + FUEL_DESCRIPTION

linmod04 <- lm(SPECIAL_TAX ~ CATALOG_PRICE+FUEL_DESCRIPTION, data = toyota)

summary(linmod04)

Call:

lm(formula = SPECIAL_TAX ~ CATALOG_PRICE + FUEL_DESCRIPTION,

data = toyota)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-4868.7 -819.6 -220.4 945.8 17536.0

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 3.387e+02 5.520e+02 0.614 0.540

CATALOG_PRICE 2.593e-01 8.267e-03 31.366 < 2e-16 ***

FUEL_DESCRIPTIONELECTRICITY -6.734e+03 4.261e+02 -15.803 < 2e-16 ***

FUEL_DESCRIPTIONLPG -1.989e+03 1.571e+03 -1.266 0.206

FUEL_DESCRIPTIONPETROL -2.051e+03 4.608e+02 -4.451 1.12e-05 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 1520 on 392 degrees of freedom

(3 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.8335, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8318

F-statistic: 490.5 on 4 and 392 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16This model is not really an improvement compared with the former model.

The data set is not a random sample from all registered cars in the Netherlands; it is a random sample from registered cars from three brands, KIA, BMW and AUDI; because of didactic reasons, KIA PICANTO’s are excluded from the sample.↩︎